|

| Illustration: Benedicte Rossi |

Can video games help stroke survivors rebuild the broken links between brain and body? James Urton examines the promise and pitfalls. Illustrated by Benedicte Rossi.

Maggie Reynolds sighted her target on the laptop screen and inhaled. Her eyes darted between the screen and her upright fist. She struggled, trying to raise her fist a few inches higher. But the desires of her brain couldn’t connect with her muscles. She failed, and the laptop made a percussive clunking sound. She lowered and massaged her numb left arm, fist still clenched.

Reynolds looked over at Luke Buschmann, the lanky UC Santa Cruz graduate student who sat nearby on a sofa. He focused on a mathematics textbook balanced on his knees. Buschmann hadn’t noticed her struggle, or that Reynolds still had good news to share. “That was my highest score,” she boasted.

They sat in her living room in Aptos, California, that January day so Reynolds could try out a motion-sensing video game that Buschmann developed to help people like her. Four years ago, a massive stroke on Christmas Day robbed Reynolds of control over half her body, but not her zeal. As she spoke about her love of the sun, the violin and Arizona, she sat alert in her ruby-red wheelchair. Under her faded auburn hair, her face creased with decades of laughter. But below her neck, her movements were one-sided. “I had a bleed on my right hemisphere, so I lost my left side,” she said. “The bleed just destroyed an immense area of my brain.”

In a stroke, a blood clot or a hemorrhage cuts off the flow of oxygen to part of the brain. Within minutes, that region shuts down. A century ago, stroke survivors were encouraged to lead quiet, still lives. Today, fueled by overwhelming evidence of the brain’s natural “plasticity” to resurrect old pathways and bypass damage, modern therapies try to get stroke survivors moving again.

The 72-year-old Reynolds is determined to take back every inch of territory she lost. Her left side is too weak for some traditional therapies. Reynolds hopes Buschmann’s creation will open the door to virtual therapy that will help her get closer to the life she left behind. Buschmann hopes Reynolds will guide him toward effective game-based rehabilitation to keep bodies moving, brains engaged, and hearts fixed on reclaiming lost ground.

One-sided therapy

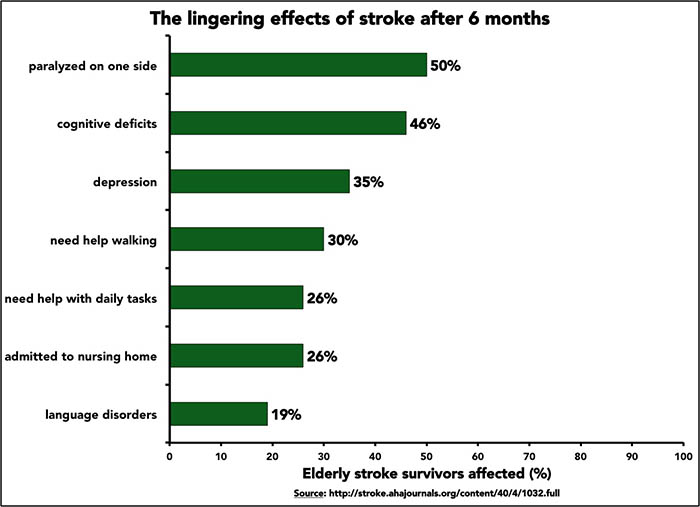

Nearly 800,000 people suffer strokes each year in the United States. Up to 75 percent of survivors report lasting physical impairments, which vary based on where and how severely the stroke damaged the brain. Some survivors are left numb or paralyzed on one side, a condition called hemiplegia. Others, like Reynolds, claw back limited use of their weak side through aggressive therapy.

|

Graphic: James Urton |

Stroke therapies attempt to balance the general needs of all stroke survivors with the unique needs of each patient, says neurologist Daofen Chen of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Maryland. For many hemiplegic stroke survivors, doctors and physical therapists often recommend constraint-induced movement therapy. Restraints hold a patient’s good arm in a cast, sling or modified glove for hours, forcing the stroke survivor to use his or her weak side. Such rigorous therapy can help restore strength, dexterity and range of motion in an affected limb. Scans show that the brains of these patients add new gray matter to damaged areas within weeks.

|

But this forceful and coercive approach doesn't work for all hemiplegic survivors. It does not help people like Reynolds, who is too weak on her left side. Further, in a recent survey more than two-thirds of stroke survivors admitted they were “unlikely” to comply with the rules of constraint-induced movement therapy. It took too much time, required too many office visits or simply was too frustrating, they reported.

Buschmann and his advisor, UC Santa Cruz computer engineer Sri Kurniawan, aimed to test whether motion-sensing games could motivate stroke survivors to help themselves heal. “Can we rely on internal motivation?” asks Kurniawan. “Can we design the game so that they would be persuaded to use the weak side?”

Researchers, doctors and physical therapists have hoped for more than two decades that virtual therapies might work. Games have been designed for neurological conditions such as dementia and multiple sclerosis—as well as hemiplegia. Many studies show promise. But the myriad of options for game designs and the individual needs of patients make virtual therapy hard to test. There are even options for tactile interfaces and direct-brain stimulation. “The technology is still emerging and evolving,” stresses Chen.

Buschmann needed to see how well his games worked and whether stroke patients would like them. To that end, Reynolds and four other stroke survivors invited Buschmann into their homes to try his creations in five sessions over a two-week period.

|

Photo: James Urton |

| Maggie Reynolds at her home in Aptos, California. |

|

The set-up was simple. In Reynolds’s house, everything fit neatly on one end of her dining table. A laptop went up front. Behind it sat a black, book-shaped device about one inch thick. Its spine lay horizontal to the table with three small circular lenses aimed at Reynolds: the Kinect system, the motion-sensing interface that captured her body movements, processed them and relayed them to the laptop. Reynolds could choose from among four games to play for 20 minutes. Each game lasted four minutes, and Reynolds could play any combination she wished.

Recovery—and learning

The Stroke and Disability Learning Center lies on the edge of the Cabrillo College campus in Aptos, about five miles from Reynolds’s home. On clear mornings, sunlight streams in through a grove of trees across the street. The main hallway is filled with the sounds of teacher instructions, student laughter and furniture sliding on linoleum floors.

Most attendees are stroke survivors, though some have other neurological conditions. “They’re no longer patients,” says center director Cynthia FitzGerald. “They are enrolled here as students. It’s a huge boost to self-confidence when so much of life has changed.”

About 150 men and women take courses at the center each semester, usually at the urging of a primary care doctor. Center staff review each student’s case and recommend courses, including mobility, speech, memory and calisthenics. Students also can take ceramics, painting, singing, dancing, yoga and oral history. “We don’t have any competitors,” says FitzGerald. A handful of other programs associated with colleges or universities “generally focus on mobility. There’s nothing that is comprehensive.”

Buschmann first came to the center to volunteer at the computer class. When he and Kurniawan decided to design a game for stroke survivors, he turned to Lenny Norton, a physical therapist who teaches at the center.

Norton crafts his classes around movement—“getting them so they can get up and out of a chair, walking, balancing,” he says, sitting on an exercise ball at his desk. Norton showed Buschmann the basic movements that hemiplegic stroke survivors often struggle with. He taught Buschmann how physical therapists measure range of motion and strength and helped him recruit the five survivors who tested his games.

Buschmann designed his games so players could switch arms in the middle of a game, a novel addition. Two subjects with profound hemiplegia used their unaffected arms for all the games. Two other players, who had milder hemiplegia, switched freely between arms to rest their weak sides. Reynolds used her weak arm 80 percent of the time. The Kinect scanned each player’s upper body, noting the position of the head and neck, as well as the shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand of each arm. Occasionally, when Reynolds’s weak arm became difficult to control, she would use her strong arm to steer it. “Every once in a while a bad word comes out,” she confesses.

Buschmann created his first game by modifying a basic keyboard-and-mouse game from an open-source website. He simplified the background, added music and sound effects, and adapted it for the Kinect system. From this first game, Buschmann made three more. A month later, he set it up in five different homes within a few miles of UCSC.

A desire to help people drives the Staten Island native. “I think there are enough people in this world designing weapons,” Buschmann muses. “I would like to devote my time to something decent.” He spent months reading about virtual therapies and proposing ideas to Kurniawan. She would usually ask him to come back with more proposals. He thought, played guitar at the beach, and kept at it. He considered virtual approaches for blind, hearing-impaired, or dyslexic people before settling on hemiplegic stroke survivors.

Virtual promises

Many other researchers see promise in virtual therapy. But the field hasn’t matured—even after 20 years. “There’s a lot of evidence to show it’s effective, but how much more effective is still in question,” says Mindy Levin, a virtual rehabilitation expert at McGill University in Montreal. The variables for designers and researchers—from consoles to patients—make it almost impossible to compare different games and neurological conditions. But these options also make virtual therapies adaptable to each patient’s needs. “In virtual reality we can modify the practice to fit the person,” Levin says.

The arm-switching option Buschmann built into his games appealed to Maggie Pasquetti. A stroke nearly three years ago left her with hemiplegia. But the 62-year-old’s medical insurance didn’t cover comprehensive therapy for her upper limbs. She used self-taught exercises to improve coordination in her weakened left arm, but she yearned for more. “I’d really like to get this arm so I can do more than just hold a can or open a loaf of bread,” she says. Her motivation is evident. In one game, Pasquetti and another user with mild hemiplegia used their weak sides 80 percent of the time.

|

Photo: James Urton |

| Maggie Pasquetti at her home in Aptos, California. |

|

The three volunteers who could play Buschmann’s games with either arm used their weak sides more than half the time. After two weeks, the ranges of motion in their shoulders improved. Buschmann wants more hemiplegic stroke survivors to try the games; three players are not enough, he says.

Buschmann also wants to understand how personal motivation affected the games. He designed his games to go faster when a player used his or her stronger arm, reasoning that the added difficulty would prompt players to rely more on the weaker arm and the easier game settings. But one player with mild hemiplegia relished the more difficult setting—and used her good arm even more. Buschmann hopes other designers take this into account. Making virtual therapy more rewarding is critical, he says, but only if this motivation helps patients use their affected sides.

Virtual therapy has its critics, often from within the field. Opinions differ on the proper place of virtual approaches, but many agree they should not replace sessions where patients receive face-to-face treatment, guidance and encouragement.

“They’re a tool. It just depends on how you use it,” says neuroscientist Joaquin Anguera of UC San Francisco. “You can use it right or wrong.” Anguera uses video games to study cognition and multitasking among the elderly. His caution stems from virtual rehabilitation’s uncertain place in medicine.

“You’d have to prove that [virtual therapy] is better than a very good therapist giving you years of traditional therapy,” stresses neurologist John Krakauer of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. No large-scale study has measured whether virtual therapy really helps treat neurological conditions. “You need large trials with lots of controls,” adds Mindy Levin. “And a lot of money.”

Some believe the lack of a large comprehensive study is holding virtual rehabilitation back. Others favor the current piecemeal approach. “It may be a bit early,” cautions Chen. “A well-controlled large-scale study will not be easy, even if certain technology shows [promise].” Patients with the same neurological condition are affected in different ways, making a large-scale study difficult, says Chen. But Chen and Levin laud the flexibility of virtual therapy and its potential as a tool to enhance existing therapies.

Krakauer supports virtual therapy under limited circumstances. He argues that patients need intense, aggressive and repetitive therapy right after a stroke, when the brain’s ability to repair itself is primed and ready for action. Most stroke therapies today, including virtual approaches, miss this repair window. “I appreciate the spirit of it, and it has all the ingredients of promise,” he says. “But ultimately it’s not going to go anywhere” without making use of this sensitive recovery period, Krakauer asserts.

Podcast produced by James Urton. Click on image to play.

New pathways

In a perfect world, Krakauer’s blunt criticisms would spur change. Patients like Pasquetti would have better health care coverage. Reynolds would have been in physical therapy sooner. Every stroke survivor would receive a combination of in-person and virtual therapy to establish and repeat aggressive exercises hundreds of times to help the brain reconnect with the body.

Buschmann’s games could help create this world. Hope lies in how the stroke survivors played his games. They took on each one, even the games that frustrated or challenged them. Their internal motivation to make progress drove them to keep at it. Buschmann’s games—bolstered by new options to strengthen limbs, improve flexibility and change settings—might have potential in living rooms beyond California's central coast.

If all stroke survivors started aggressive, in-person therapy within days of their trauma, they would make the most of the brain’s natural window to repair itself. Afterward, when survivors go home and continue therapy with periodic office visits, the flexibility and durability of virtual therapy could be a great asset. “Find out how they like to play the game, what their favorite settings are,” Buschmann says. “That’s a way you can motivate people.” One volunteer loved Buschmann’s baseball video game because he was a former athlete. Reynolds loved another game because of its sound effects. Properly applied, these small motivations could be seeds of effective virtual therapy—the difference between doing an exercise a dozen times and quitting, and completing it 200 times each day until the brain bypasses dead zones and builds new neural connections.

Constraint-induced movement therapy fails when patients don’t like the restrictions. Switching on virtual therapy may be the upgrade they need.

© 2015 James Urton / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Top

Biographies

James Urton James Urton

B.A. (biology) Augustana College

Ph.D. (molecular and cellular biology) University of Washington

First job: Science writer, University of Washington news office

Science snared me early, and it was a natural fit. I was that annoying kid who loved books about dinosaurs, evolution and astronomy. I thought the natural world was fun and quirky, and I could not shut up about it. My folks bought a set of encyclopedias, which I monopolized as my new vehicle for exploration.

I became a biologist and entered the laboratory. I probed the genetic secrets of spiny fish, mustard weeds and fuzzy protozoa. But research left me unfulfilled.

Quietly, I began to explore. I spoke about science to community and church groups, dabbled in blogging, and found myself as happy as I was when I had my nose buried in those encyclopedias. Dinosaurs are back on the table, as is the rest of nature. I'm ready to be annoying again.

James Urton's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Benedicte Rossi Benedicte Rossi

Ph.D. (neuroscience) Université Paris 6, France

Internship: Gladstone Institutes, San Francisco

I am a science illustrator with a passion for nature, biology and research. I have a Ph.D. in neuroscience and was a researcher before I decided to mix art with science. Today I like to help convey scientific concepts and results with illustrations and figures. When I am not working you can find me reading or hiking and camping with my family.

Benedicte Rossi's website

Top |