A furtive glance, a nervous

chat, and finally you dare to ask that girl for her phone number. When

you meet her on a first date, you will wear your best shirt and your new

Italian shoes, and when you drive her to the new Greek restaurant your

car will be freshly waxed. When humans date, they do pretty fancy stuff

.

Some

animals, however, do even more stunning things. For bragging rights, certain

male lizards develop bright orange scarves around their necks. Because

these capricious ornaments are biologically costly for the lizards, male

lizards try to impress females by showing that they are strong enough

to waste some of their energy on fancy displays, says Barry

Sinervo, a behavioral biologist at the University of California, Santa

Cruz (UCSC). Indeed, many animals and humans show off their strength by

flashing these seemingly inefficient and wasteful signs. It’s a form

of conversation that not only rules dating but also many other conflicts,

such as wage negotiations between unions and firms. Some

animals, however, do even more stunning things. For bragging rights, certain

male lizards develop bright orange scarves around their necks. Because

these capricious ornaments are biologically costly for the lizards, male

lizards try to impress females by showing that they are strong enough

to waste some of their energy on fancy displays, says Barry

Sinervo, a behavioral biologist at the University of California, Santa

Cruz (UCSC). Indeed, many animals and humans show off their strength by

flashing these seemingly inefficient and wasteful signs. It’s a form

of conversation that not only rules dating but also many other conflicts,

such as wage negotiations between unions and firms.

This is the conclusion of

a group of researchers who call themselves game theorists. The researchers

use games like poker as metaphors to try to explain strategies that conflicting

parties use when they either disagree or try to persuade their opponents

to adopt their own points of view. Economists were the first to use mathematics

to model such situations. They view trading situations as games between

consumers and sellers, and wage negotiations as matches between unions

and companies. Later, scientists from different fields started using the

same models and helped to move the field forward. For instance, evolutionary

biologists explained the strange dating behavior they observed in lizards

and birds using game theory.

One of the most important

conclusions of game theorists dealing in both biology and economics is

that arguing parties notoriously distrust each other. Whether you are

a lizard or a shareholder, you’ll have to make a hell of an effort

to ensure that your opponent believes you. This is because in trading

and dating, being dishonest is often a successful strategy.

Game theorists have found

that in many everyday situations people behave like poker players in a

gambling hall. A good gambler lets other players at the table believe

that his hand is unbeatable. For this strategy to succeed, it is essential

to stay cool at all times. Calmness is the secret of fortunate gigolos

and triumphant poker players alike. One involuntary tick of the eyelid

can ruin a gambler’s day, because it’s a sign of weakness that

may cause the others to raise the stakes.

"Poker is a classic game

where different people have different information," says Wilson,

an economist at Stanford Business School. "If you are a player in

poker you know the cards you have. That’s your private information,

your wealth," he says. Wilson found that the rules of play in poker

are similar to many human situations of conflict. In his work, he aims

to describe how unions and companies behave in wage negotiations and labor

strikes.

"Like in poker, the difference

in information between the parties is the usual source of the difficulty

in reaching an agreement," he says. Company owners know how wealthy

their firm is, but the union doesn’t. So whatever the shareholders

say, the employees have no reason to believe them. Opening the books to

the union won’t do the job; there are too many tricks to hide money.

"It’s cheap talk, it’s not believable," says Wilson.

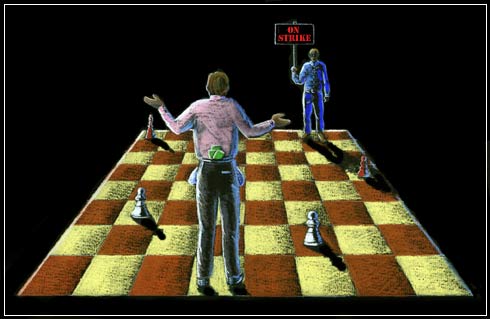

"A strike is a process

of signaling," Wilson says. During the wage negotiations that usually

precede a strike, the stances of the parties are obvious. The union asks

for wages that the company doesn’t want to pay. The workers argue

that they need more money to feed their families. The employers reply

that if they paid higher salaries, the firm might go bankrupt.

Wilson used the 1994 players’

strike in major league baseball as a model to find general rules of how

people compete and disagree. The strike shook the world of sports and

put a serious damper on fans’ enthusiasm for the World Series. When

club owners tried to explain their financial situation, they drew scenarios

of bankruptcy and disaster. But the players didn’t believe them.

So there was no way for an easy settlement, and painful and expensive

walk-out was inevitable. Wilson found that many of the mind games that

poker players employ where also used in this and other strikes.

As a tool to strip conflicts

of their emotional aspects, he used the mathematics of game theory. The

models he developed can explain why wage negotiations between workers

and employers sometimes escalate into a strike. During a strike, negotiations

are usually halted. But Wilson thinks this silence is an effective way

of telling each other the truth.

In a strike, two parties of

decision makers collide. But they can’t choose their strategies independently.

To be successful they have to figure out what the other party’s next

move is. And in that sense, every negotiation is a game.

What separates labor negotiations

from poker is that there are no obvious rules of play. In the former,

conflicting parties define the allowed moves and countermoves ambiguously,

if at all. In a poker game, players raise the stakes to find out how good

a competitor’s cards are. But in wage negotiations, only a strike

will reveal what the company’s wallet really looks like.

A closer look at the press

coverage of the 1994 baseball strike yielded plenty of evidence for Wilson’s

theories. "We owners didn’t have much credibility. The players

simply didn’t believe us when we told them we were feeling economic

stress," Giants’ president Peter Magowan told the San Francisco

Chronicle.1. "Baseball is financially healthy. The claim of widespread

disaster is pure fiction," said players’ consultant Peter Noll

in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, confirming Magowan’s

assumption .2. Players just did not believe club owners, because there

was no way for them to get their hands on credible sources of information.

Unions and employers often

don’t talk to each other at all during the initial phase of a strike.

Enduring the strike is nerve-wracking. As on a first date, the ability

to stay cool separates the men from the boys. A prosperous firm that has

hidden money from the union during the wage negotiations will get nervous

after the first few days of a strike. Soon its managers will realize that

raising wages is cheaper than enduring the strike any longer. However,

the workers who can’t sustain their families with their old salaries

have little to lose. They will stay away from work until the company submits

a better offer. Because for both of them the strike gets more expensive

every day, endurance is a sign of honesty. "The signaling between

the two parties is the dominant feature, and endurance serves as a credible

signal," says Wilson.

The signals that the negotiators

exchange are costly, and hence they are credible. A bluffer gives up sooner,

because it is simply too expensive to mimic the strategy of an honest

player. Only the poker player who does not bluff, or can afford to lose

a lot of money, will agree to raise the stakes above a certain limit.

When the time is ripe only the self-confident lover will say ‘’here’s

looking at you, kid’ without making a fool of himself.

Being cooler than your opponents

is what counts. In the game of "chicken," which game theorists

use to model such situations, two drivers head toward each other at high

speed in the hope that the other will swerve first. The worst outcome

of the game is a crash, or a jump over a cliff as in James Dean’s

"Rebel without a Cause." In a labor walk-out the choices and

their respective payoffs and costs bear striking similarities to "chicken."

In a strike, however, the

worst-case scenario is that the company goes bankrupt - not usually through

the price of higher wages, but due to the cost of the strike. Both the

union and the firm would profit when their opponent "chickened out"

first and cooperated with their wishes.

To prevent an outcome that

is a catastrophe for both parties, players observe each other very carefully.

But opponents send out signals on other levels, too. In poker it is not

only the cash put on the table that can prove a gambler’s sincerity.

A bead of sweat on the opponent’s forehead can tell you that his

"full house" is only a pair.

A subtle signal like this

helped to end a 1994 faculty strike at Hebrew University in Israel. The

professors, dissatisfied with their salaries, stopped teaching. After

initial offers, the Israeli government and the union couldn’t reach

an agreement. The professors went on strike and refused to negotiate for

eight weeks. Then a key faculty vote at Hebrew University revealed that

98 percent of the professors were willing to pursue the strike much longer.

Government officials realized that the professors weren’t sweating

a drop - they were ready to go all the way. Shortly after that a better

offer was on the table, which put an end to the students’ holidays.

The settlement in Israel was

a compromise between the two parties. Neither the government nor the professors

were fully satisfied, but they were content enough to return to business

as usual. Both players were motivated to minimize their concessions. In

the end, though, neither party ended up eating the cake all on their own,

but both of them tried to get the bigger piece nonetheless.

Paul Povel, an economist at

the University of Minnesota, says that Wilson’s work is an essential

contribution to the understanding of how people negotiate. "Wilson’s

model to interpret patience as an honest signal will be a valuable tool

to explain many other examples of conflicts too, " he says. "One

problem we will have to solve in the future is to develop mathematical

equations for these situations to make more accurate predictions."

"For me Wilson is a candidate

for the Nobel Prize," says Alvin Roth, an economist at Harvard University.

"His work on strikes is really earthshaking."

Because in the beginning of

a labor strike no party has a reason to collaborate, game theorists refer

to this situation as a "non-cooperative game." John Nash, a

mathematician at Princeton University, made such disagreements accessible

to mathematics. For his achievement, which he published in 1950, he was

awarded the Nobel Prize in economics more than 40 years later, in 1994.

For 20 years after he published

it, nobody realized how important Nash’s triumph was. But suddenly

the penny dropped. "This literature then just sort of exploded during

the 70s and ’80s," says Wilson. "Economics was almost revolutionized

by game theory," he adds.

Economists soon understood

how fundamental their game theory-based mathematical models were and that

the concepts serve totally different purposes. "In the 70’s

economists realized that many biologists were interested in very similar

problems," says Povel. "They contacted them and said ‘Hey,

we developed some fancy equations that might solve your problems."

Soon researchers of different fields started to have tete-a-tetes, which

led to an odd phenomenon: some leading economists started to publish their

results in The Journal of Theoretical Biology. Biologists read

these papers and realized that game theory might help answer questions

they hadn’t yet addressed.

One such example is the observation

that the male of a given animal species often looks totally different

from the female. In humans those differences are subtle. Both sexes look

very similar. But when it comes to certain exotic bird species, males

and females look so different that at first glance nobody would suspect

that they share the same nest. This so-called sexual dimorphism was one

of the biggest unsolved mysteries of biology for many decades.

What puzzled biologists the

most was the fact that males of certain species developed traits that

didn’t seem to make sense. Some male birds, like the peacock, developed

such long tail feathers that they could hardly fly. Why would a bird want

to trade his flight machinery for a trendy costume? Why human playboys

wrap silk scarves around necks is obvious, but in a world where survival

of the fittest is the name of the game, these opulent decorations seemed

odd. Then, behavioral biologists started to use the game theory models

offered by economists. They found that birds and lizards use capricious

traits in the same way that gamblers and strikers show off their coolness.

Birds and lizards use deluxe dresses and elaborate colors to show how

strong they are.

The premier goal of a male

animal, however, is not to get higher wages, but to create as many offspring

as possible. The measure of success is not money, but access to females.

To fertilize as many females as possible, a male has to attract them and

scare off potential rivals. Males who manage to signal their strength

faithfully will achieve both of these goals at the same time.

Some lizards have developed

a special way to look good and show off their force. UCSC’s Barry

Sinervo studies male side-blotched lizards in the Coast Range of California.

The strongest and largest of them have bright orange necks. Orange-type

males are 20% longer and have 50% more of the sex hormone testosterone

circulating in their blood. "They are bulky, like football players,"

says Sinervo. "We call them usurper males; they can literally dust

the others in battles," he adds.

The orange color, which dyes

their necks, serves as a badge of status. "Badges of status evolved

because they are honest indicators of a male’s ability in a conflict,"

says Sinervo. "The badge makes the orange male not to have engage

in contests with other males that are of lower quality." Weaker males

can’t afford to be orange: they are blue. But they don’t fail

to recognize the flag. "They are terrified by the orange color,"

says Sinervo.

The orange color is a precious

commodity in nature. The dye is made of carotinoids, which the animals

can’t synthesize themselves. Rather they have to take it from the

food they eat, which means that they use part of their energy uptake for

showy effects. Thus only strong males can afford to use energy for decoration.

But the investment pays off, because blue males don’t even think

of trying to beat up an orange.

But for the usurper males

the orange color also serves another purpose. "It’s probably

also a signal to the females," says Sinervo. He thinks that the message

macho lizards have for their females is: "I am so healthy, I’ve

got so much of these carotinoids around, so I can actually afford to show

off a little."

Because females want to have

healthy kids, they look for a healthy mate. And in a test series, Sinervo

and his colleagues found that the orange males’ immune systems indeed

did better fighting diseases. "It’s yet another game - it’s

a mate choice game," says Sinervo. In this case the purpose of the

super males’ orange scarf is to be handsome.

Yet, the usurpers can go too

far. If they dominate the population too drastically, the females may

suddenly switch their attention. They start choosing males of different

colors, who apply less aggressive strategies.

The orange male does not always

get all the dates. When there are too many machos out there, females prefer

the more decent characters. Environmental changes cause the line between

good and bad, cool and uncool, and between brave and fearful to dwindle.

There are more than two parties and each of them has a different strategy

and each of them can be successful under certain conditions.

Sinervo thinks the future

of game theory will be used to explain contests like those in which not

only two but many players participate. Many two-way games, such as labor

strikes, are more complex than they appear to be. "In strikes the

company actually has to worry about competitors," Sinervo says. In

the beginning of a poker game more than two players participate. Each

of them might have a different strategy.

Just as in some seasons slimmer

lizard males are en vogue, tastes are variable in humans, too. Bulky males

and jocks are not always popular with all females. Although ideals of

beauty sometimes seem to converge to archetypes, the fact that we all

look different shows that the mating game is complex.

And accordingly the systems

of signals has many levels. The real challenge for the players is to search

for the truthful indicators of status. Bad players try to hide information

the way a gambler covers his lousy pair. Voiceless signals, however, will

reveal how much trouble he really is in. A tiny bead of sweat is enough.

At other times players shout, out their messages loudly using flags like

shiny colors or cars.

Game theorists are on the

verge of understanding these silent messages. They are beginning to hear

the speechless chat that influences many of our decisions, by holding

their mathematical stethoscopes on the breast of our behavior.

More mathematical research

is needed before game theorists will be able to come up with models that

explain complex behavioral games in detail and give us advice.

But next time you are paying

the bill in that Greek restaurant, before you are walking your date back

to your freshly waxed car, remember that you are basically behaving not

much sophisticated than a bulky orange lizard.

.1 San Francisco Chronicle,

15 September 1994

.2 Wall Street Journal, 15

September 1994

|